The area contains an extensive Egyptian archaeological site that represents the remains of the capital city newly-established and built by the Pharaoh Akhenaten of the late Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1353 BC), and abandoned shortly afterwards. The name for the city employed by the ancient Egyptians is written as Akhetaten (or Akhetaton - transliterations vary) in English transliteration. Akhetaten means "Horizon of the Aten."

Descending the Nile, as we follow its flow from south to north, we leave Thebes behind. After admiring the Temple of Hathor at Dendera, the sanctuaries of Osiris at Abydos, the Coptic monasteries at Sohag, we arrive at Tell el Amarna, on the east bank of the Nile. There we set foot on a vast desert tract limited to the east by the first foothills of the Arabian mountain chain.

Today, nothing remains of this dream, lest it be the occasional wall segment or levelled column section. Lost to oblivion, Tell el Amarna has disappeared under the sands. Not only was this epic deed itself forgotten, but an anathema was pronounced on the person at its origin, Amenophis ( also spelled Amenhotep) IV Akhenaten. For almost three thousand years, his name was stricken from memory, with nothing but a total blank in its place. The defender of universal justice, peace, contemplation and fervor, was rejected by the very people to whom he had dedicated his life. His friends, even some of his relatives, and his people, relentlessly attacked his memory, razed his capital, mutilated his effigies, going so far as to hammer out his name from the walls of tombs that he himself had ordered to be dug. His unforgivable crime had been that of daring to defend the dignity of Man, of asserting his identity.

The people's hate bore fruit, since none of our usual sources of information - royal lists or archives - mention Akhenaten; not the Abydos Table, nor the Royal Papyrus of Turin, nor even Manetho's Chronology.

However, in the preface to the 1988 edition of one of the great monographs devoted to the Amarna drama, "Akhenaten", Cyril Aldred, its author, writes: "The character and deeds of King Akhenaten [...] continue to engross and mystify historians. From being one whom his people did their best to forget, he has become[...]the celebrated subject of novels, operas and other works of the imagination." His reinstatement owes all to those whose studies, whose passion above all, contributed to casting out the ancient curse, thus allowing Akhenaten to regain his former innovative status with respect to the universal conscience of humankind.

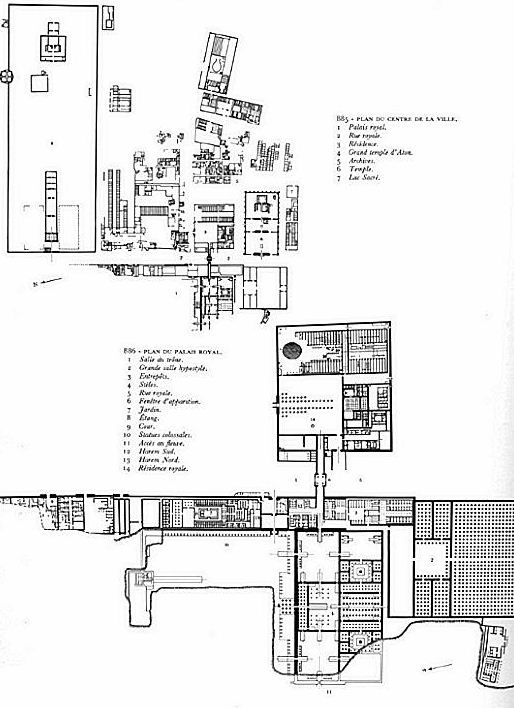

Ninetheenth-century travellers, mostly monks, hardly ever stopped over there. The French draftsman Nestor L'Hôte (1828 expedition under Champollion and 10 years later on his own account) was content to sketch several of the Boundary Stelae  he came across in the neighboring desert. Finally, the great Prussian expedition directed by Richard Lepsius made an immense survey of the site in 1843. The Denkmaler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien published from 1849 to 1859 were a compilation of all the plottings of the Nile valley monuments made by the team's draftsmen; the third division (Vol. VI, pages XCI-CLXXIII) devotes twenty-one plates to the Amarna remains. Connoisseurs of the period thus discovered, much to their amazement, the strange facial features of the banished king. The very dry style proper to such highly scientific presentations notwithstanding, the subjects dear to the Amarna artists were at last revealed: the king being acclaimed by the throngs along the streets as he wends his way to the shrine, the king making an offering to the Disk, the royal family in the privacy of their apartments, the bestowing of favors upon the court's high officials. Above all, the city's temples and palaces were represented in plan, or to be more exact, at once in plan and in elevation, that is synthesized, in such detail that they served the archaeologists to confirm their own on-the-site discoveries.

he came across in the neighboring desert. Finally, the great Prussian expedition directed by Richard Lepsius made an immense survey of the site in 1843. The Denkmaler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien published from 1849 to 1859 were a compilation of all the plottings of the Nile valley monuments made by the team's draftsmen; the third division (Vol. VI, pages XCI-CLXXIII) devotes twenty-one plates to the Amarna remains. Connoisseurs of the period thus discovered, much to their amazement, the strange facial features of the banished king. The very dry style proper to such highly scientific presentations notwithstanding, the subjects dear to the Amarna artists were at last revealed: the king being acclaimed by the throngs along the streets as he wends his way to the shrine, the king making an offering to the Disk, the royal family in the privacy of their apartments, the bestowing of favors upon the court's high officials. Above all, the city's temples and palaces were represented in plan, or to be more exact, at once in plan and in elevation, that is synthesized, in such detail that they served the archaeologists to confirm their own on-the-site discoveries.

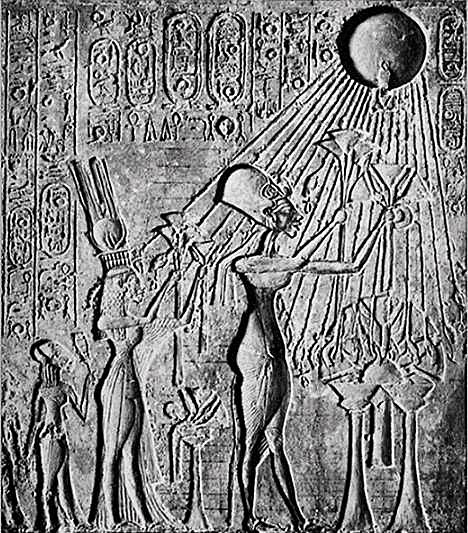

18th Dynasty - The royal family being blessed by the Aten - Limestone - H 0.332 - Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum - This stela undoubtedly belonged to one of Akhenaten's domestic altars

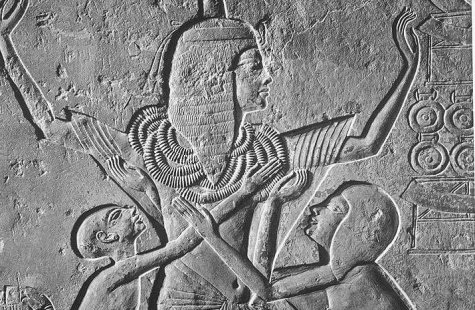

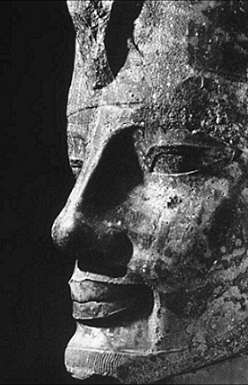

18thDynasty - Sculptor's study for the profile of Akhenaten -Limestone - H 0.144 - Provenance unknown - Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum

Fifteen years later, a small volume "freely translated from the English" but published without naming an author, under the title Les Antiquités éyptiennes, provides a revised canon of the royal lineage. By comparing the lists drawn up by Manetho and "the names of kings(...) found on the monuments," the author suggests, beside Amenophis-Memnon and Horus, three new cartouches: Aak-en-Aten-Ra or Amenhept II, brother of Horus - Titi, his sister, the wife of Ay- Amuntuanch, brother of Horus. This is perhaps the first modern mention of the name of Amenophis IV Akhenaten, and of Tutankhamon and Nefertiti. Despite his having been identified, Aak-en-Aten, or Khu-en-Aten as he was called at the time, continued to intrigue the learned of the day. The King's singular morphology, especially, inspired the strangest hypotheses: the French Egyptologist Mariette, soon to give full vent to his imagination in the libretto for Aïda, saw Akhenaten as a Sudanese slave castrated by his masters and set on the throne as the outcome of a dramatic coup d'état. To Lefébure, on the other hand, he was a woman disguised as a man, a royal usurper succeeding his/her father Amenophis III, identified as the Horus to which Manetho refers.

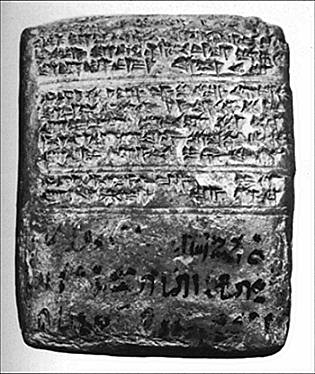

Finally, one June day in 1887, a peasant living in the vicinity of Tell el Amarna took up her daily task of digging in the mounds of mudbrick debris in search of sebakh, the nitrous compost used by the village people in Egypt to fuel the fire. At the foot of a levelled wall, she discovered hundreds and hundreds of clay tablets covered with mysterious signs. Stacking a few of them in her veil, she showed them first to the neighbors, and then to a local official who, as a figure of authority, was expected to have all the answers. Apparently, this particular one was too imbued with himself to cast an eye at a few modest briquettes, so he had the petitioner led away. But determined as she was to make a few piasters out of her discovery, our peasant woman loaded her son and two donkeys with all the tablets she could muster and journeyed to Luxor, in the hopes of encountering a less arrogant mamur. Upon her arrival, alas, all that was left in one piece in her bundles were several dozen tablets, for the rest had been reduced to dust along the bumpy road. She showed two of them to an inspector who, at last, did take the matter seriously and had the samples studied. To the general astonishment, it turned out that she had come up with the diplomatic archives belonging to the court of Amenophis IV. What a bitter disappointment it was, then, when the poor soul had to admit that four/fifths of her load had been wiped out. Of the full lot, only three hundred fifty tablets were salvaged. But at least the site itself was back on the map!

Tablet No. 23 (British Museum), sent by Tushratta of the Mitanni to Amenophis III, to inform him that the goddess Ishtar of Nineveh had been sent off to Egypt.

In 1891/1892, Sir Flinders Petrie began a first season of excavations: he unearthed a major part of the royal palace, the administrative buildings and, more to the south, several private houses. He thus uncovered a unique set of secular paintings that had adorned the royal apartments, including two exquisite little princesses, since transferred to Oxford's Ashmolean Museum

From 1902 to 1903, with frequent interruptions due to international conflicts, the site was occupied by several exploration teams: the Egypt Exploration Fund, the Deutsche Orient Gesellschaft, and the Egypt Exploration Society under the direction of J. D.S. Pendlebury, in charge of the excavation publications.

The highly competent works published by the scholars who, as of the end of the nineteenth century, took a keen interest in the Amarna Period, have granted the world much insight into the dramatic high points of that era. Nonetheless, many questions still remain to be answered: Akhenaten and his court continue to hold on to much of their mystery.

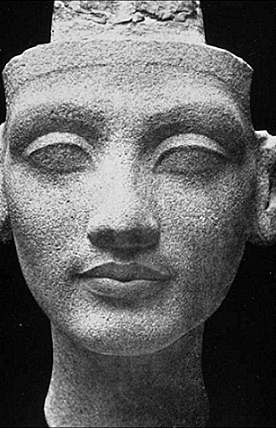

18thDynasty Head of a colossus representing Amenophis III - Quartzite - H 1.177 - From Luxor London, British Museum

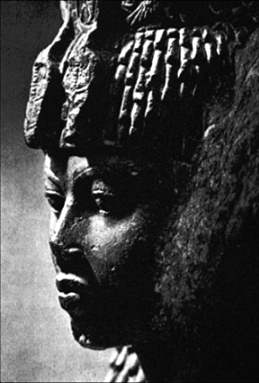

Black basalt head of Amenophis III

Black basalt head of Amenophis IIIThe historical evidence is very scant but, luckily, a comparative interpretation of the documents that survived the post-Amarna Period repression has allowed specialists to solve some of the enigmas: Around 1425 BCE, Thutmose IV, the grandfather of Akhenaten, married a princess from the Mitanni; the latter took the Egyptian name of Mutemwiya upon arrival at the royal court. At some distance from there, in the provinces - more specifically, near to today's Akhmim, the capital of Upper Egypt's ninth nome, a local squire, Yuya, took his cousin Tuyu as spouse. The couple settled in Thebes a few months after their wedding, where both embarked on a glorious court career: in addition to his titles as Prophet and Superintendent of the Cattle of Min, Yuya became the King's Lieutenant of the Chariotry and Master of the Horse; while Tuyu took on the title of Superintendent of the Harem of Amon.

18thDynasty - Head of a statuette representing Queen Tiye - Gray schist - H 0.072 - From the Sinai region, Cairo, Museum of Archaeology

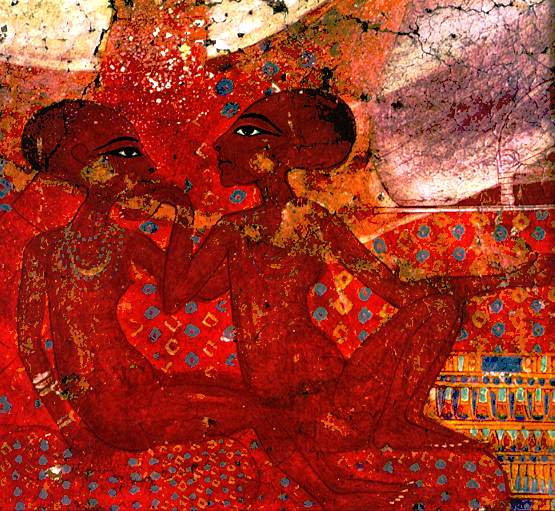

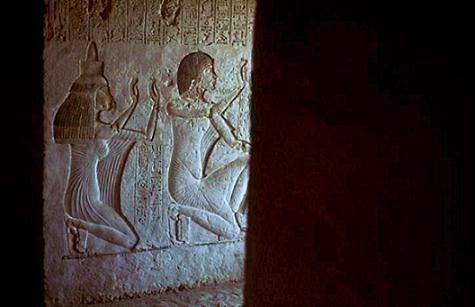

18thDynasty - Tiye, the wife of Ay, in festal attire - Low relief from the first corridor - Tell el Amarna, civilian necropolis, the tomb of Ay

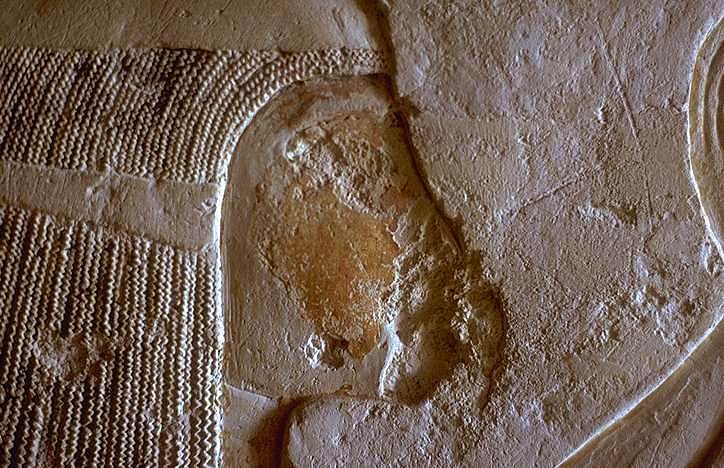

detail

detail

detail

During the some thirty-eight years of their actual reign, Amenophis III and Tiye had a great number of descendants: first, an heir - Thutmose - who died prematurely, then Amenophis, the future Amenophis IV Akhenaten, and Smenkhkare. Their daughters included Princess Sitamun and, later, Tutankhamun, who was to succeed her older brother, and Beketaten, the youngest, "dear to his father's heart."

18thDynasty- Unfinished bust of Nefertiti - Sandstone - H 0.292 - From Tell el Amarna, Berlin (East), Bodemuseum, Ägyptische Sammlung - Excavations conducted on the workshop of Thutmose at Amarna unearthed this bust, which still shows the artist's brush reference marks.

Seven years after coming of age, Amenophis, heir apparent, and subsequently co-regent, married the legendary Nefertiti. Mystery crops up again here: who was she? Some identify her with Tadukhipa, the daughter of Tushratta, King of the Mitanni, saying that her foreign origin comes through in the Egyptian name she chose upon settling in Egypt: Nefertiti, the Beauty who came, implying from elsewhere. Tempting as it might be, this hypothesis does not hold up against serious examination, for certain documents indicate that Tadukhipa arrived at Malkata in the year 36 of Amenhotep III's reign, which falls quite some time after the attested date for the marriage between Nefertiti and Amenophis. Those inclined to orthodoxy would see her rather as a late descendant of Amenophis III and Tiye - that is, a princess - in order to meet with the requirement of royal blood in one who would wed an heir to the throne: but nowhere is their mention of Nefertiti as a daughter of a king. Might she have been the offspring of the king and one of his secondary wives? Hardly, for if her mother had been of royal lineage, Nefertiti would have obeyed custom by mentioning her name in the official records, something she never did. We are thus obliged to admit that Nefertiti did not belong to the reigning family. At times, she is pictured as a young queen in company of her wet-nurse Tey, wife of the Father of the God Ay. If Ay, one of the highest ranking members of the court, received, beside the countless honorary titles and roles he accumulated, the epithet Father of the God, it is undoubtedly because he begat a child associated with the royal lineage. In fact, eveything leads us to believe that Ay was Nefertiti's father. The fact that Tey never was called Mother of the God, but wet-nurse, does not endanger this hypothesis, for she was probably Ay's second wife, playing the role of governess and mentor to the young queen. The recent discovery of a chapel devoted by Ay to the god Min in the region of Akhmim allows us to carry the hypothesis one step further: the Father of the God was undoubtedly very closely related to Yuya. Their similar careers and, even more, their shared attachment to the ninth nome of Upper Egypt, incite us to believe that Ay was Yuya's son and, hence, brother to Queen Tiye. Although not of the blood of the gods, Nefertiti would thus be nonetheless linked to the reigning family through her father, becoming Tiye's niece. Her marriage with the heir to the throne would then comply in all aspects with Egyptian custom.

Nefertiti and Amenophis IV gave birth to six daughters: Meritaten, who married one of Amenophis IV's brothers, Smenkhkare; Maketaten, who died as a young adolescent; Ankhesenpaaten, who was granted in mariage to Prince Tutankhaton, and who later became Queen of Egypt under the name of Ankhesenamun; Neferneferuaten-Tasheri; and, finally Neferneferure and Setepenre, of whom nothing is known.

18Dynasty - Nefertiti making an offering to the Aten - Low relief from the antechamber - Tell el Amarna, civilian necropolis, the tomb of Mahu

In the first place, Akhenaten did not invent the Aten. His name appears as early as in the Old Empire Pyramid Texts, where it is listed under the Litanies as one of the avatars of Re, manifested in the form of a Disk. Moreover, it is a fact that worship of the Disk took root in Thebes well before Akhenaten's arrival on the scene. It seems that Tuthmosis IV already embraced this old Heliopolitan doctrine with great fervor. Although one cannot go so far as to say he abandoned the official cult of Amon (also spelled Amun), it is interesting to note that he was one of the first pharoahs of the New Empire to recognize the authority of Re, thus linking up with an already millenary theological system. By having the famous "Dream Stela" carved between the paws of the Giza Sphinx, he asserted that he owed his throne to Re-Harakhty, Re of the Two Horizons: "I shall give you," the god says, "royalty on earth at the head of the living, you will wear the White Crown and the Red Crown." Thus, at a time when orthodoxy still held a firm grip, Amon was deprived of his basic right of deciding for himself who was worthy of manifesting him on earth, who was his son the sovereign. After Thutmose IV, Amenophis III went even a step further, as testified by a block found in the foundations of the tenth pylon at Karnak. Here the king is shown in the company of the same Re-Harakhty, designated as the "Jubilant in the Horizon in his name of Shu which is the Aten." Why, one wonders, did this return to the doctrines of Heliopolis occur. Most certainly it was an attempt by the kings to escape the Amon clergy, whose members were becoming more insolent by the day and were gradually taking over everything. But beyond this, it was above all out of a need for authenticity, as experienced in the learned circles of the capital towards the end of Dynasty 18. Under the influence of Amenophis-son-of-Hapu (who, in turn, belonged to the Heliopolitan colleges), the ancient writings were re-studied, the old rituals re-honored. We know, for instance, that the celebration of Amenophis III's first jubilee instigated an enormous compilation one month prior to the event, in order to ensure that everything would take place in the right tone. There is much reason to believe that all the painstaking research involved allowed theologians to rediscover the pure source of early sun worship, long since eclipsed by the cult of Amon. This could only lead to the reassertion of the primordial deities Re-Harakhty and the Aten.

If in effect, then, Akhenaten did not invent the Aten, but merely adopted the ideas of his forefathers, where does the heresy lie? It lies with the fact that he claimed it as absolute, devoting himself exclusively to celebrating the Aten and proclaiming himself prophet thereof by adopting the epithet ur mau, from Chief Prophet, as borne traditionally by the highest pontiffs of Heliopolis. As master of the rituals, he asserted himself as the living aspect of the Aten, identifying with that god to the point of having himself represented, in the upper part of the civil stelae, as the unique vehicle of popular piety. Nefertiti and the royal daughters were subsequently linked to this myth: the familiar scenes uniting the king, the queen and the princesses in the intimacy of their apartments are not in the least anecdotal: their figuration was intended as a reminder that, beyond his basic unity, the Aten is at once father, mother and child - that is, the principal creator and creature.

Hand of Akhenaten making an offering to the Aten - Sandstone - H 0.235 - From Ashmunein - New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

As a child of the Aten, Akhenaten assumed the prerogatives which, until that time, had been reserved to the prohets and grand priests. And, truly a first in Egyptian history, he even claimed to guide his people along the way to revelation. Many a courtier from Tell el Amarna had the stelae at the entrance to their tombs carved with the boast of "having been taught the doctrine by the King himself" or "having listened to the doctrine day by day from the lips of the King himself."

Divested of their basic powers, the traditional clergy openly challenged the King, transforming what might have been but a positive cleansing of the dogma into a fierce battle for prestige between partisans of the Heliopolitan tradition and the upholders of Theban orthodox doctrine. The struggle gradually grew into a conflict between Re in his aspect of the Aten and Amon, and, finally, between the King and the priests. It was at this point that matters became dramatic, since Akhenaten, forced into a defensive position by the events, had to adopt a policy that was certainly more intransigent than he would have desired: in his fourth regnal year, he changed his name from Amenophis, Satisfaction of the Aten, to Akhenaten, Acting Spirit (that is, incarnation) of the Aten. Less than two years later, he left Thebes to found, "at a site belonging to no god or goddess, to no sovereign, to which no one had any rights," a new capital, a new epicenter of his authority, Akhetaten, Horizon of the Aten.

Aak -en-Aten

The period during which the King set up his court at Tell el Amarna coincided with extremely serious troubles in Thebes: the holy city's temples were shut down, its priests banned from office. All images of Amon were desecrated, and his name and epithets hammered out; his wife Mut was subject to the same fate. Indeed, fanatics beyond all limits, the partisans went so far as to break into the necropolises to erase, at the very bottom of the tombs, all mention of that contemptible god. Still others heaved themselves up to the top of the obelisks to attack the sun symbols. Evidence was even found of a scribe who had gathered together all the archival documents under his responsibility in order to wrathfully cross off all the words in any way analogous to the names Amon and Mut; not even the word mut, mother, was spared! Akhenaton could do nothing to avoid having his own father Amenophis's cartouches defiled. The cult of the Aten was hardly the love doctrine it purported to be!

18thDynasty- Levelled remains of one of the colonnaded corridors of the North Palace, called the Palace of Nefertiti - Tell el Amarna, city of Akhenaten

Despite being subjected to destructive attacks early in the century, the Boundary Stelae the King had set up to demarcate his territory - and they alone - continue to speak out of times past: Akhenaton's kingdom covered a territory the size of "six iteru, three-quarters of a khe and four cubits the side," - from the north stela to the south stela - or about thirteen thousand meters. They also proclaim that "His majesty mounted a great chariot of electrum,and, on the favorable day, marked out the limits of the site he had named The Horizon of the Aten; then, as men, women and all things rejoiced, he had set up an altar and made an unprecedented oblation to the Aten. Then, all those near to the King, the high-placed officials, the army chiefs, were brought before him and bowed low to him although he asserted that it was the Aten Himself who had designated this site (...), to which the court replied that Aten would unveil his plans to no one but him alone and soon all the nations of the world would come here to bring Aten, giver of life, the tribute they owed to him. Then the Pharoah had raised his hand towards the Disk at its zenith and had vowed he would build Akhetaten there for Aten his father, at this precise site and nowhere else; that he would listen to no one, not even the queen, should one try to persuade him to build Akhetaten elsewhere. Then he had listed all the grand and beautiful monuments he planned to set up, the House of the Aten, the Mansion of the Aten, the Pavilion for the Queen, the House of Rejoicing for the Aten in the Island "Exalted in Jubilees", and all the other buildings and works necessary to celebrate the Aten, the Apartments of the Pharoah and the Apartments of the Queen."

The foundations for most of the buildings listed in the royal text have been identified, in particular the Great Temple (House of the Aten) and the Smaller Temple (Mansion of the Aten) of the Aten, the vast palace onto the back of which were built the administrative buildings, the House of the King or Little Palace, the Apartment of the Queen. Above all, an eight hundred meter stretch of the royal street that ran through the center of the city has been cleared. Beyond this stretched the leisure quarters, the homes of the high-ranking officials, and further to the north, the suburbs, a complex mosaic of tightly grouped, small houses.

The city of Akhetaten

- North Palace, called the Palace of Nefertiti

- Great Temple of the Aten

- Royal Palace

- Central Quarter

- South Suburb

- North Tombs

- South Tombs

As everywhere in Egypt, and since time immemorial, private homes were built of light materials - mudbrick, pisé and wood. Stone, which was reserved for the houses of the gods and the dead, only rarely was used except for door jambs and column bases. The German research teams brought to light the levelled remains of several of Akhetaten's dwellings: they were square or rectangular in plan, except for the porter's lodge which jutted out at the building's northern angle. The three sections into which a residence was divided comprised reception rooms, opening onto a vast hall whose ceiling was supported by polychromed wood columns; parlor rooms, also grouped around a salon that almost always included a brick bench serving as a couch; and finally, to the rear of the dwelling, private apartments, featuring varying number of rooms, small salons, resting rooms, powder rooms, wardrobes, reserved to the house master and mistress. Each residence was competed by outbuildings and a flower garden, enchanced by a lake and pavilions or kiosks. Of course, the foundations that have been rediscovered hardly do justice to the serene harmony of the Amarna Period homes, with their sparkling, whitewashed walls featuring the subtle polychromy of decorative painted friezes: lotus bouquets, papyrus bunches, from which tightly packed flocks of wild ducks and geese shoot out. It was so long ago that the sands swept over and buried the gentle life in harmony with the Unique One.

In order to bring back those who lived such a life - who took care of the royal house, directed the administrative centers, kept watch over the rituals within the sanctuaries, or operated the vast estates that spread as far as the eye could see - one must travel to the foothills of the Arabian mountains, where the hypogea of those faithful to the king were dug: Meyre, High Priest of the Disk; Ahmose, the King's Private Secretary and beloved companion; Ramessu, steward of the House of Tiye; Pentu, the King's physician and nearest to the King; Parennefer, His Majesty's only friend; Mahu, Chief of Police; Tutu, Pinhasy, May, Ipy, and others still.

The tombs have come down to us in a most disastrous state. Not a single one, not even that of the divine Father Ay, the most lavish of them all, was ever completed, much less occupied, since the entire court went back to Thebes just a few months after the King disappeared. All that is left to discover are partially hewn pillars, naked walls, the mere outline of reliefs, a rare polychrome notation. And, nonetheless, here and there a magnificent sketch carved directly in the rock by the steady hand of the outline scribe. Sadly, in their wrath against the heretic, the Theban partisans sent quarriers down to the very bottom of the caves with their mallets to pound, mutilate and desecrate the images of the Aten, the representations of royalty or civilians, and even the hymns accompanying them, in order to erase for all eternity and in all minds any memories of the schismatic King.

The layout of the Amarna tombs is faithful to tradition, comprising - just like the Theban hypogea, for instance - an entrance hall, a large square or rectangular pillared room, and an axial chapel sheltering the statue of the deceased, completed by a shaft leading to the sarcophagus room. On the other hand, the iconography of the reliefs or paintings, is deliberately otherwise, devoid of all the usual references to the traditional funerary myths. The Opening the Mouth ceremony, the entombment, the pilgrimage to Abydos were all banished, as was any allusion whatsoever to the Book of the Dead or any related texts. Nor is there any mention of the great deities of the Western Kingdom - Osiris, Isis, Nepthys, Anubis, Hathor or Upuat. By contrast, and in accordance with royal doctrine, the Aten, Father and Mother of Life and of Death, is omnipresent, always accompanied by the King and the Queen, his living manifestations. The Amarna artists thus favored five major topics, which crop up systematically in the necropolis tombs:

- The royal family in adoration before the Aten: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their daughters making offerings and pouring libations to the Disk, whose rays end in hands that send the sign ankh to their nostrils, symbolizing the breath of life and, by the same token, divine inspiration.

18thDynasty - The royal family in adoration before the Aten - Limestone - H 1.373 - From Tell el Amarna - Cairo, Museum of Archaeology - This relief was removed from the King's tomb during the excavations conducted in 1891/92 - The royal family in its privacy : the King and Queen sit face to face on simple rest stools, almost always accompanied by their daughters

, Meritaten

, Meritaten , Maketaten and Ankhesenpaaten.

, Maketaten and Ankhesenpaaten.

- Visits to the shrine : the King and Queen cantering off on their grand parade chariot, followed by the court equipage and preceded by an armed escort of outrunners, on their way to the pylon of the sanctuary where a college of priests awaits them; further on, the king is shown at the foot of the altar, celebrating the Disk.

- The awarding of reward gold or the induction ceremony : leaning out from the Window of Appearances of the royal palace, the King and the Queen are shown bestowing the gold sign - in the form of heavy ceremonial necklaces- to high-ranking officials, for distinguished service. The court and, at times, the foreign ambassadors pay hommage to the royal couple, while the relatives and servants of the beneficiary dance with joy.

Bestowing the reward necklaces on General Horemheb - Limestone - H 0.772 - From Saqqara, Leyde, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden - This relief was unearthed from the Memphite tomb of Horemheb, general under the reign of Akhenaten

- The receiving of tributes : the King and the Queen, dressed in their festal attire, and seated on a richly ornamented throne set up under the royal baldachin, receive the foreign delegations from Nubia, the land of the Kush, the provinces of the Fertile Crescent, the faraway lands of Asia and the Aegean. At their feet lies a pile of rare products from their countries - goldsmith pieces, elephant tusks, pelts, essential oils, exotic fruits, and skilfully conccocted flower bouquets.

Occasionally, artists would replace the official subject matter with an event that had marked the career of the deceased: the visit of Queen Tiye to Amarna and the inauguration of the new temple of the Aten for Huya, for instance, the inspection of the temple shops for Meyre, the details of a particularly sensational lawsuit for Mahu.

But it is in the margins of the large pictures above all that Amarna art showed itself to its best advantage, in the crowd of small figures who, seemingly indifferent to the main action, exalt the joy of living under Aten's law in picturesque scenes. Here, without being distracted by the passing of a royal parade, a young woman gathers several flowers along the roadside; there, at the very gates of the palace, a rascal flees from a farmyard where he has stolen a few eggs. And over there, a servant screams and chases a mischievous little puppy who irked his mistress. Indeed, it is the serene celebration of universal harmony, in which the humblest participates, that represents the real victory of the cult of the Aten. Despite the many humiliations, setbacks, and failures life held in stock for his people, Akhenaten brought them hope. His teaching was that fervor, faith or, more simply, willing joy at each moment, could lead man back to the ineffable light of the Disk, the ineffable indulgence of God, awaiting at the end of his/her life road. In the debris of the unoccupied royal tomb, there remain scattered fragments of the chest that was to house the King's entrails: the four tutelary goddesses, traditional guards of the canopic vases, are replaced by four falcons with spread wings, as if to show that, after his death, carried by the divine birds, Akhenaten knew he would forever live in the bosom of the Aten his father.

Allegedly written by Akhenaten himself, around 1360 BCE, this hymn of love and fervor conveys a vibrancy unparalleled in all the literature bequeathed to us from Ancient Egypt. Several versions and variations were discovered in the devastated tombs of the Tell el Amarna dignitaries. Below you will find the main excerpts from the completest version, found in the tomb of Ay:

« Thou arisest fair in the horizon of Heaven,

O Living Aten, Beginner of Life.

When thou dawnest in the East,

Thou fillest every land with thy beauty.

Thou art indeed comely, great, radiant and high over every land.

Thy rays embrace the lands to the full extent of all that thou hast made,

For thou art Re and thou attainest their limits

And subdues them for thy beloved son.

Thou art remote yet thy rays are upon the earth.

Thou art in the sight of men, yet thy ways are not known.

When thou settest in the Western horizon,

The earth is in darkness after the manner of death.

Men spend the night indoors with their head covered,

The eye not seeing its fellow.

Their possessions might be stolen, even when under their heads,

And they would be unaware of it.

Every lion comes forth from its lair

And all snakes bite.

Darkness lurks and the earth is silent

When their Creator rests in his habitation.

The earth brightens when thou arisest in the Eastern horizon, [...]

Thou drivest away the night when thou givest forth thy beams.

The Two Lands are in festival.

They awake and stand upon their feet

For thou hast raised them up.

They wash their limbs, they put on raiment

And raise their arms in adoration at thy appearance.

The entire earth performs its labors.

Thou appointest every man to his place and satisfiest his needs.

Everyone receives his sustenance and his days are numbered.

Their tongues are diverse in speech [...]

And their color is differentiated,

For thou hast distinguished the nations.

Thou makest the waters under the earth

And thou bringest them forth [as the Nile] at thy pleasure to sustain the people of Egypt

Even as thou hast made them live for thee,

O Divine Lord of them all, toiling for them,

The Aten Disk of the day time, great in majesty!

All distant foreign lands also, thou createst their life.

Thou hast placed a Nile in heaven to come forth for them

And make a flood upon the mountains like the sea

In order to water the fields of their villages.

How excellent are thy plans, O Lord of Eternity!

- a Nile in the sky is thy gift to foreigners

And to beasts of their lands;

But the true Nile flows from under the earth for Egypt.

[...]

When you rise you stir everyone for the King,

Every leg is on the move since you founded the earth.

You rouse them for your son who came from your body,

The King who lives by Maat, the Lord of the Two Lands,

Neferkheperure, Sole-one-of Re,

The son of Re who lives by Maat, the lord of crowns,

Akhenaten, great in his lifetime;

And the great Queen whom he loves, the Lady of the Two Lands,

Nefer-nefru-Aten Nefertiti, living forever.!!»

- Wikipedia

- Photographic Collection → Advanced search → Museum → Ägyptisches Museum → Akhenaton