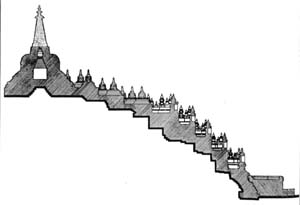

Before studying the monument itself, it is interesting to consider the original name for which the musically reso nant "Borobudur" - usually translated as "temple on the hill" - serves as an abbreviation: "Bhumisan Brabadura". The latter translates into "The Ineffable Mountain of Accumulated Virtues", a highly symbolic title, liturgically speaking. For Borobudur was conceived as an initiatory mountain, to be ascended level by level by those seeking the enlightenment that corresponds with the unity of the shrine's top. The plan is extremely simple: a multitude of pagodas, stupas, and niches

characterize the lower levels, with a single stupa crowning the whole. The path hence leads from multiple to oneness.

located at the four cardinal points.

Before examining the shrine's plan in cross section, a brief explanation of its philosophical context is called for. Borobudur is a direct reflection of Mahayana ("great vehicle") Buddhism which, during the 1st century BC, evolved from other sects called "Hinayana" ("lesser vehicle"). By contrast to the body of strict doctrines set up by Buddha himself, and spread by his disciples and the community of monks, Mahayana Buddhism took in the influences of various sects over the centuries. It is a "constituted" religion incorporating thousands of cosmogonic, philosophic, and religious variants.

Before examining the shrine's plan in cross section, a brief explanation of its philosophical context is called for. Borobudur is a direct reflection of Mahayana ("great vehicle") Buddhism which, during the 1st century BC, evolved from other sects called "Hinayana" ("lesser vehicle"). By contrast to the body of strict doctrines set up by Buddha himself, and spread by his disciples and the community of monks, Mahayana Buddhism took in the influences of various sects over the centuries. It is a "constituted" religion incorporating thousands of cosmogonic, philosophic, and religious variants. Mahayana Buddhism projects a cosmos where the world is seen as an enormous sort of plateau afloat in the Absolute, in astral and cosmic voids. This plateau is organized into a system of concentric circles with, at its center, a mountain so magnificent, high, pure, and divine, as to be beyond human perception: Mount Meru.

Literary references to Mount Meru speak of an ineffable site atop which Buddha sits in totally inwardly turned concentration: his eyes are closed, for he is awaiting the end of the cycle of humanity before opening them and casting judgement. Over the cosmos as a whole there exists the immanence of God, in the strictest sense, and below Mount Meru, we find the first circle, entirely subtle/floating, termed by Westerners as the sky. Next comes the solid circle, the earth, followed in turn by the liquid circle, the earth's bodies of water. These three are demarcated as the perceptible world by a boundary of fire which, in the Buddhist cosmos, is located at the end of the seas. Thus, we have the unknowable at the top - a Mount Meru visible to Buddha alone - followed by four circles of the tangible world accessible to man: air, earth, water, and fire. Beyond fire, lies once again the ineffable, in the form of circles of milk, molasses, alcohol, etc. that provide the tangible world with energy.

Literary references to Mount Meru speak of an ineffable site atop which Buddha sits in totally inwardly turned concentration: his eyes are closed, for he is awaiting the end of the cycle of humanity before opening them and casting judgement. Over the cosmos as a whole there exists the immanence of God, in the strictest sense, and below Mount Meru, we find the first circle, entirely subtle/floating, termed by Westerners as the sky. Next comes the solid circle, the earth, followed in turn by the liquid circle, the earth's bodies of water. These three are demarcated as the perceptible world by a boundary of fire which, in the Buddhist cosmos, is located at the end of the seas. Thus, we have the unknowable at the top - a Mount Meru visible to Buddha alone - followed by four circles of the tangible world accessible to man: air, earth, water, and fire. Beyond fire, lies once again the ineffable, in the form of circles of milk, molasses, alcohol, etc. that provide the tangible world with energy.

In all lands once touched by Buddhism, the most beautiful and highest mountain is named Mount Meru; the name has been popularized nine times in China, three in India, etc.

In short, the bottom circle is strictly an account of life experiences

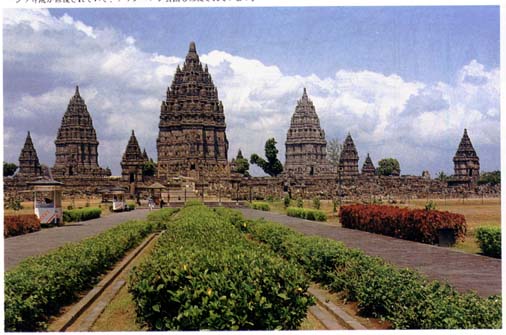

The Sailendra dynasty is said to hark back indirectly to India by being cousins to the Chandella dynasty, which left numerous monuments in India between the 7th and 8th centuries (most notably, the Khajuraho temples). Allegedly, a schism in the family occurred between those remaining faithful to Hinduism - the Chandella dynasty, which stayed in Khajuraho - and the Sailendra branch which, having converted to Buddhism, set off for Indonesia as early as the 4th century. The Sailendra dynasty reached its zenith in Indonesia during the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries. Their king was considered the founder of Borobudur; he bore the name Indra (Hindu god represented on an elephant - god of rain, monsoons, storms and winds). The fact that the founder of this most fabulous Buddhist shrine bore a Hindu name shows the ambiguity of the Sailendra dynasty's position between Buddhism and Hinduism. The shrine was actually signed or co-signed by Indra's son, King Samaragunta (also spelled Samaratunga). The latter turned the com pleted monument over to the Buddhist monks, who enjoyed royal sponsorship. Just as in classical India, in Java the dynasties generally continued Hindu names and beliefs. At the same time, they opened their minds to Buddhist doctrines, effecting a sort of unofficial Leur conversion

. An amazing feat indeed. The same margin of religious tolerance exists to this day in Japan, where the majority of people are born and married according to the rites of Shinto, the land's native religion, but die comforted by Buddhist ritual.

. An amazing feat indeed. The same margin of religious tolerance exists to this day in Japan, where the majority of people are born and married according to the rites of Shinto, the land's native religion, but die comforted by Buddhist ritual.

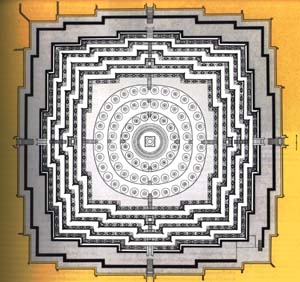

The plan for this stupa is a schematized representation of the cosmos, a mandala.

In the vernacular Indian language Pali, "mandala" means: sacred drawing. In a ritual held in common by Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, the faithful meditate by carrying out repetitive drawings on the ground of certain mandalas handed down by tradition and believed to bring awareness of the divine. The Buddhists developed this art to the greatest extent. Tibetan, Nepali or Sikh art exhibitions provide occasion to admire the "thangkas": these are large paintings that, hung by monks over statues of Buddha, represent the fruit of the spiritual exercise of reproducing a divine mandala. Thangkas are not considered works of art since, once finished, they lose their importance: for worshippers who produce these works, what matters is "doing the drawing", and not the end product. Such worshippers accomplish the same rite as the monks who become painters, illustrate manuscripts or untiringly draw and repeat mandalas on the ground. The mandala featured here is the oldest and most orthodox extant; it is of Hindu rather than Buddhist origin, and explains the origin of the world.

This beautiful notion of the reaction of the gods to disorder is widespread. Thus "Atoum" lost patience with the disorder of Noun; by analogy in Western tradition, it could even be said that the Lord himself set about organizing our world, separating the liquid from the solid, for instance. In similar fashion then, the Veda gods descended upon Purusha to fasten it to the ground, so that the creation of the world could get under way.

And that is just what we see in this mandala diagram: the circle, which is the most dynamic of shapes, represents original chaos, or Purusha, while the square symbolizes the net with which, according to legend, it was immobi lized by the Veda gods. The circle, contained within the square, is the origin of All. In Vedic Hinduism, this man dala represents the organization, creation - and thus potential - of the world. Buddhism, Jainism, and many other religions are branches of this early Hinduism, so it comes as no surprise that Buddhism held on to this idea: the square in fact symbolizes the absolute, and the circle the dynamism of the absolute. It is between inertia and mo tion that the world, in all its complexity, was born. Or, in other words, at the center of all things lie at once, the heart of Purusha, that is all that is to become, and the heart of the gods, all that is absolute. Hence, the first day of creation sits at the center of All, similar to the core of a volcano. In Buddhism, this is represented by the great central stupa.

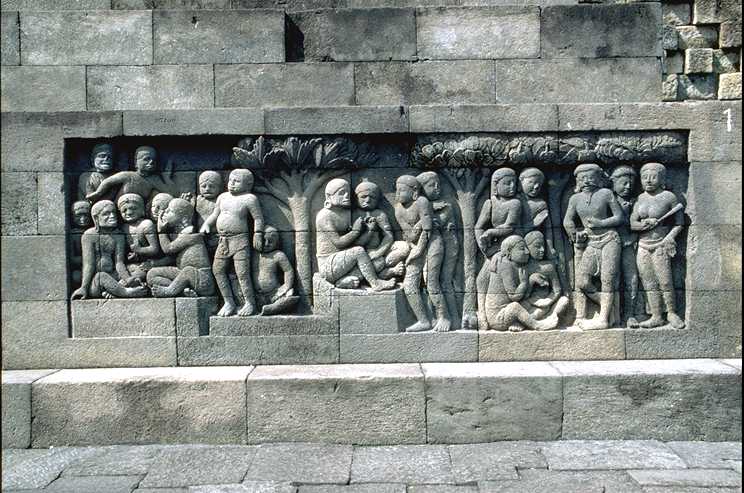

The most intricately adorned level (of which one sees little since it was encased almost at its origin in stabilizing stones) features 160 carved panels depicting human joys and despair of the World of Desire. The 1300 bas-reliefs along the balustraded corridors of the square galleries forming the next five levels of terraces - the World of Form - represent scenes and teachings from the life of Buddha and the lives of 43 Bodhisattvas

: at this level, it is assumed that a person has achieved some mastery over worldly desires. Finally, the three circular terraces are left un adorned except for the 72 perforated stupas, each containing a statue of Buddha: this World of Formlessness cul minates in the bell-shaped but totally unadorned central stupa that is Nothingness and All.

Since around the 12th century, Borobudur lay forgotten, abandoned to the destruction wrought by dense tropical vegetation and earthquakes. The construction came almost completely loose, gradually turning into a shapeless mound. A most-deserved tribute thus belongs to those who recognized the grandeur of Borobudur and contributed to its restoration for the world to enjoy: including Sir Stamford Raffles, C. Leemans, Theodoor van Erp and, most particularly, UNESCO.

It is a classic Buddhist ritual for pilgrims to carry out the stages of a visit by turning clockwise and gradually up wards around a stupa, until reaching the smallest round, which is that of the unity at the top. This method was already described in pre-Vedic texts prior to 2700 BC; in India

.

Following in the footsteps of various discoverers

. Its story begins with the discovery of the grandeur of Borobudur by, interestingly enough, an Englishman, as early as in 1815 (when Java was under British colonial rule): Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. In London in 1817, Raffles published the first engravings showing the site and the first bas-reliefs which were extremely comical (and which, unfortunately, have never been reproduced elsewhere). The engraver, a Brit on of London, had never visited the monument; dissatisfied with Raffles' draftsmanship, he transformed his work into Greek Neoclassic versions, which brings us to our present image: it could be mistaken for the altar of Perga mum!

No major restoration was undertaken until the end of the 19th century: the first was instigated by a specialist from Leyden (since Java was by then under Dutch colonial rule), Dr. C. Leemans. Due to limited financial resources, Leemans saw to the most urgent needs, and if the monument was able to be rescued a century later, it is in large part thanks to Leeman's initiative. The first truly large-scale restoration was carried out between 1907 and 1911 by a Dutch second lieutenant and engineer, Theodoor van Erp. However, none of these specialists encountered the problem of pollution and stone rot plaguing the monument more recently. A comparison betweena photo taken of Borobudur in 1910 and one in 1960

. Its story begins with the discovery of the grandeur of Borobudur by, interestingly enough, an Englishman, as early as in 1815 (when Java was under British colonial rule): Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. In London in 1817, Raffles published the first engravings showing the site and the first bas-reliefs which were extremely comical (and which, unfortunately, have never been reproduced elsewhere). The engraver, a Brit on of London, had never visited the monument; dissatisfied with Raffles' draftsmanship, he transformed his work into Greek Neoclassic versions, which brings us to our present image: it could be mistaken for the altar of Perga mum!

No major restoration was undertaken until the end of the 19th century: the first was instigated by a specialist from Leyden (since Java was by then under Dutch colonial rule), Dr. C. Leemans. Due to limited financial resources, Leemans saw to the most urgent needs, and if the monument was able to be rescued a century later, it is in large part thanks to Leeman's initiative. The first truly large-scale restoration was carried out between 1907 and 1911 by a Dutch second lieutenant and engineer, Theodoor van Erp. However, none of these specialists encountered the problem of pollution and stone rot plaguing the monument more recently. A comparison betweena photo taken of Borobudur in 1910 and one in 1960 shows the extent to which the stones were spotted and eroded

shows the extent to which the stones were spotted and eroded and how far its earthen core had sunk

and how far its earthen core had sunk .

.

A first restoration with the support of UNESCO was accomplished in 1948. In the sixties, an appeal from Indo nesia was answered by international support on behalf of restoration efforts carried out jointly by the Indonesian government and UNESCO. The results of this project, lasting from 1971 to 1984, are what you now see.

Another minor restoration was necessary after a bomb attack to the summit of Borobudur damaged several of the stone-latticework-surrounded stupas, alas proving that this magnificent shrine is no safer from harm than any of the other jewels constituting the cultural heritage of mankind.

Jatakas are stories about the Buddha before he was born as Prince Siddhartha.They are the stories that tell about the previous lives of the Buddha, in both human and animal form. The future Buddha may appear in them as a king, an outcast, a god, an elephant—but, in whatever form, he exhibits some virtue that the tale thereby inculcates. Avadanas are similar to jatakas, but the main figure is not the Bodhisattva himself. The saintly deeds in avadanas are attributed to other legendary persons. Jatakas and avadanas are treated in one and the same series in the reliefs of Borobudur.

The first twenty lower panels in the first gallery on the wall depict the Sudhanakumaravadana, or the saintly deeds of Sudhana. The first 135 upper panels in the same gallery on the balustrades are devoted to the 34 legends of the Jatakamala. The remaining 237 panels depict stories from other sources, as do the lower series and panels in the second gallery. Some jatakas are depicted twice, for example the story of King Sibhi (Rama's forefather).

"Un monstre attaque un navire". Histoire d'une tortue: Un Bodhisattva se transforme en tortue et sauve les naufragés puis se sacrfie pour les nourrir. 193e bas-relief des 372 de la balustrade de la première galerie (ou terrasse carrée), registre supérieur, côté ouest, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur

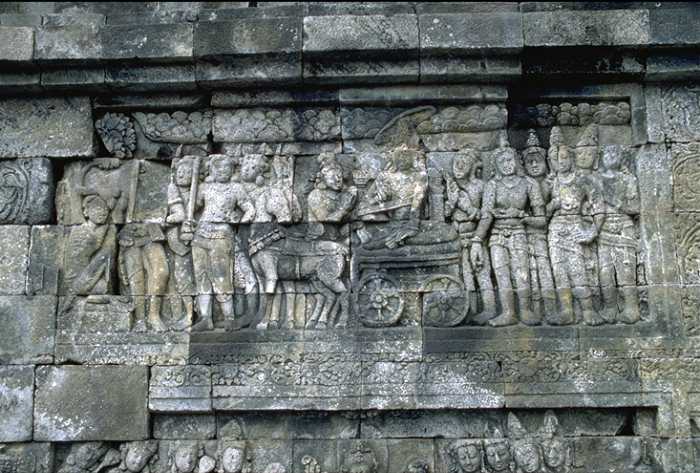

"Le roi fait proclamer sa décision au son du tambour" Contre une sécheresse, un brahmane exige du roi le sacrifice de 100 sujets. Le roi décrète choisir les plus mauvais sujets. Tous deviennent vertueux. La sécheresse cesse. 42e bas-relief des 372 de la balustrade de la première galerie (ou terrasse carrée), registre supérieur, côté est, quartier sud-est du Borobudur.

"Le Bodhisattva dans la forêt". Jataka de l'histoire du lièvre où le lièvre jure à ses amis d'offrir sa propre chair si un nécessiteux venait. Shakra apparaît mais ne tue pas le lièvre et allume un feu. Le lièvre s'y jette et renaît aux cieux. 23

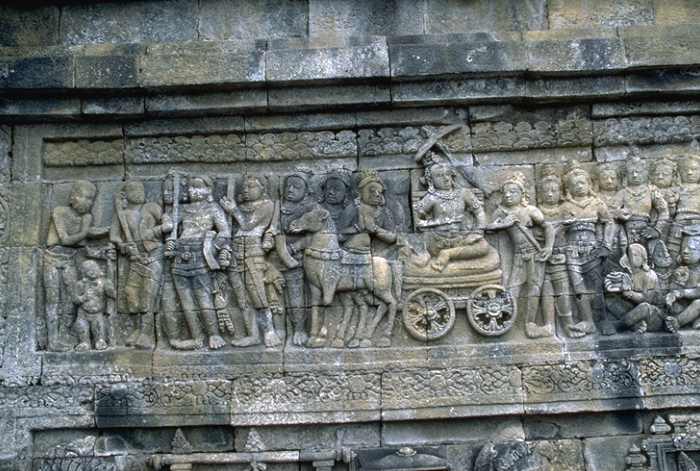

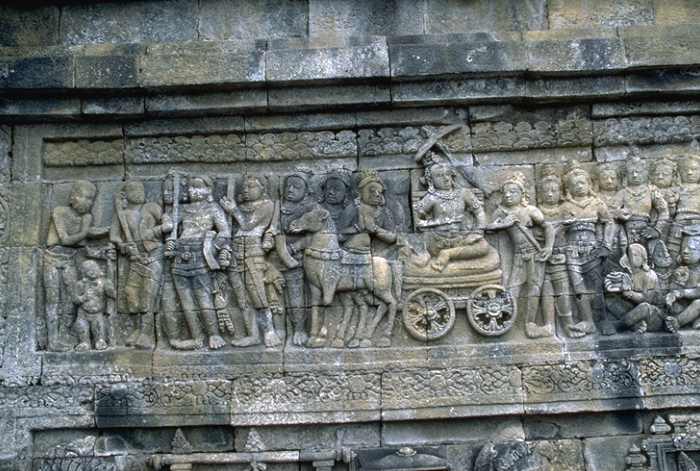

The second circle is carved with bas-reliefs illustrating a version of the "Lalita", the hagiographic account of the Buddha's life. The version presented is altogether Mahayanist, contrasting with the original concept of the Buddha as pre-existing his earthly manifestation, as first living in the heavens, from whence, at a certain moment, he decides to descend to come to the rescue of humanity. The Indian Lalita starts with the Buddha's altogether physical and prosaic birth, providing no foreshadowing of his vital predestination. The Buddha sees the light of day in the town of Kapilavastu, as the son of the town's King Suddhodana and Queen Maya Devi. At Ajanta (village in central Maharashtra, S. central India), we see this same scene representing Suddhodana's silence, which is a particularly beautiful Mahayanist idea. Suddhodana adores his wife Maya Devi, but is sad not to have children. Rather than repudiate or chase away his wife, he falls into total silence.

. He remains altogether impassive, and this is what becomes unbearable to his wife, inciting her to beseech the heavens to send her a child. Thebas-relief

. He remains altogether impassive, and this is what becomes unbearable to his wife, inciting her to beseech the heavens to send her a child. Thebas-relief illustrated here is particularly beautiful, depicting Suddhodana in a fully hieratic stance, while Maya Devi's attitude falls between restrained tenderness and a sort of humility, even guilt. The scene takes place at the well-known moment when, to the distress of their entire court, the royal couple suffers the separation imposed between them by the heirless Suddhodana's silence.

illustrated here is particularly beautiful, depicting Suddhodana in a fully hieratic stance, while Maya Devi's attitude falls between restrained tenderness and a sort of humility, even guilt. The scene takes place at the well-known moment when, to the distress of their entire court, the royal couple suffers the separation imposed between them by the heirless Suddhodana's silence.

Strangely enough, in parallel to Mary and Joseph, Maya Devi has a premonition that she will give birth to an exceptional being, while Suddhodana remains fully unaware. The moment illustrated in this bas-relief is not yet quite the Annunciation: Maya Devi - already pregnant - is shown in a reclining position at her country palace (having left Suddhodana at their city palace), where she sleeps surrounded by her attendants. She is lost in a dream

Détail du 13e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "La reine Maya rêve qu'un éléphant blanc pénètre en son sein". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur est, quartier sud-est du Borobudur

of greatness to come, in the form of a ittle elephant

- in some texts portrayed as white, in others with four or six tusks - who floats in the air supported by a lotus blossom. The importance of her dream has been underscored by the "chhatra", or parasol - symbol of royalty and imperialism - carved above her head.

- in some texts portrayed as white, in others with four or six tusks - who floats in the air supported by a lotus blossom. The importance of her dream has been underscored by the "chhatra", or parasol - symbol of royalty and imperialism - carved above her head.

In a civilization still so imbued with animism as Indonesia, dreams were considered of major significance. Scenes where the queen tries to understand the meaning of her dreams

Détail du 17e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "la reine Maya raconte son rêve au roi". Registre supérieur, 1ère galerie, mur sud, quartier sud-est du Borobudur

were far from unusual there, whereas in India, the subject was never broached. Each country of course adapted the Lalita to its own culture, but this representation of the palace is extremely interesting: indeed, no other traces of the palace architecture

Détail du 54e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha reçoit 3 palais du roi son père". Registre supérieur du mur ouest de la première galerie, quartier sud-ouest du Borobudur

of the period remain, since the brick and wood of which they were built have long since disintegrated. On the other hand, the fact that Borobudur is built of stone serves as an important piece of evidence of its status as religious architecture.

Maya's pregnancy follows its course in the best of conditions, and it is her fondest dream to give birth to her baby outside the city. She chooses a garden that is exclusively her own - a gift of the king - and it is here, in the garden of Lumbini, that Buddhist legend foresees the Buddha's birth. Thus, the queen's departure

Détail du 27e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "La reine Maya se rend au jardin de Lumbini". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur sud, quartier sud-est du Borobudu

for atop a great chariot is among the key panels.Lumbini

Détail du 27e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "La reine Maya se rend au jardin de Lumbini". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur sud, quartier sud-est du Borobudu

atop a great chariot is among the key panels.

The original Lalita foresees the Buddha's birth at the 17th hour after the queen's arrival in Lumbini, as if he would sense their arrival there. And indeed, 17 hours after their arrival, the Queen Maya Devi felt birth pains, as described in beautiful terms in the Lalita: she felt pain in her bosom and not in her womb. Feeling suffocated, and in need of catching her breath, she hangs

Le détail montrant la reine Maya se tenant à l'arbre du 28e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "La reine Maya donne naissance au jeune Siddhârtha". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur sud, angle sud-est du Borobudur.

on to a branch of a tree, at which point her womb bursts open. After the baby falls to the ground, he immediately stands up and takes four steps, one to each of the four cardinal points where, at each step, a lotus blossom is born. The central lotus blossom marking the spot where the Buddha falls to the ground, and the four blossoms at the cardinal points, form the five lotus blossoms representing Buddha's revelation. The interesting point here is that in Buddhism, the Buddha's predestination is conveyed from the very instant he appears on earth: we are immediately confronted with the renowned five points that are to become the saintly sage's five paradises. The Queen Maya Devi is often depicted grasping a tree branch - for example, at the South central India sites of Ajanta and Ellora and, in Burma, at the Ananta Temple of Pagan. By contrast, the steps taken by the newborn Buddha are rarely depicted, so this representation

is particularly rare, which makes it a shame indeed that it is in such a poor condition.

Le détail montrant les Dieux venant rendre hommage au Bodhisattva, 32e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur sud, angle sud-ouest du Borobudur.

Another panel is devoted to betrothal

Détail du 51e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha dans son palais avec ses amis et Yashodhara sa première épouse... il se réjoiut avec ses parents et amis". Registre supérieur du mur ouest de la première galerie, quartier sud-ouest du Borobudur. Jogjakarta, Indonésie

rites that are strictly Indonesian customs and totally unrelated to the classical Lalita. The subject is in fact that of prenuptial rites such as described in Western fairy tales: the handsome prince must prove himself before earning the beautiful princess. In like manner then, the poor Buddha is required to undergo a number of trials, such as a feat of archery

Détail du 49e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Encore prince, Siddhârtha s'exerce au tir à l'arc". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur ouest, quartier sud-ouest du Borobudur

, in order to marry his Gupta (Indian dynasty C. 320-c.550) princess. Another traditional test of a prince's purely physical force involves killing an elephant with but a kick of the leg (the Buddha is said to have sent the elephant right over the wall of a house). Everyone applauds the prince's exploits, and the two marry. As remarkable as it seems, this is considered a jataka.

The jatakas refer to all the legends concerning the lives of previous buddhas, in other words the lives of the Bodhisattvas. In as thoroughly Buddhist a culture as Indonesia, this chapter - which takes place prior to Buddhism - has nevertheless been fully incorporated into the story of the Buddha, which shows how difficult it has been for various countries drawn to Buddhism to remain fully orthodox.

Many mistakes were possible, and the one narrated here certainly rings false: the story of piercing seven trees with a single arrow is in fact a Hindu tale concerning the youth of Arjuna (chief hero of the Bhagavad-Gita), who accomplished the exploit to impress his own father. Yet such individual discrepancies hardly affect the overall coherence of the panels.

. Here we see the prince in the company of royal concubines reclining in his arms; one of them looks at herself in a mirror

. Most surprisingly, this same group of three reappears in a painting at Ajanta (S. central India): this pure coincidence is quite amazing, even if the story is somewhat marginal to the Lalita.

56e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Lors de sa première sortie du palais, le prince Siddhârta (Bouddha) rencontre un vieillard". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur ouest, quartier sud-ouest du Borobudur. Jogjakarta, Indonésie

. Next, he meets illness

, in the form of a skin-and-bones figure. And finally, perhaps the worst of all, he meets up with death: he sees an inert form being washed and laid out in a shroud. This is no doubt the most incisive of the three shocks the Buddha undergoes on this memorable single day.

In his incomprehension of poverty

, illness

and death

the Buddha turns to a hermit for advice. Here we see a Brahman (Hindu priest) explaining that someday we must all fall sick, grow old and die, that this is our common destiny. The explanation inspires the Buddha to seek to ease the way for his fellow man: his goal was not to erase these inevitable rites of passage, as many Western authors claim, but to smooth them.

Détail du 65e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha quitte la palais escorté par les dieux qui soutiennent les pas de son cheval". Registre supérieur du mur ouest de la première galerie, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur.

Détail du 64e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Bien que surveillé, Siddhârtha veut quitter le palais, les gardes dorment, son cocher Chandaka lui amène son cheval Kanthaka". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur ouest, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur.

: the hoofs of his horse are wrapped to ensure

Détail du 65e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha quitte la palais escorté par les dieux qui soutiennent les pas de son cheval". Registre supérieur du mur ouest de la première galerie, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur.

that his departure is noiseless, and the sentinels are drugged. In the earliest Lalita versions, the four winds - north, south, east, and west - carry the horse's hoofs. Those of you interested in comparative mythology will note that all saviors take off on flying horses: think of Perseus arriving to rescue his future wife Andromeda from the sea monster. In any case, this important event is depicted at all the major classical Buddhist sites illustrating the life of the Buddha, from Datong (China) to the Bangkok Palace.

Détail du 67e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha (Bouddha) coupe ses cheveux, insigne de sa caste noble". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur ouest, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur.

Despite his successful departure, the Buddha has a great deal of hardship ahead. For the moment he dismounts and sets foot on the ground, he must confront his own destiny

Détail du 66e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Bouddha renonce au monde et renvoie les dieux qui l'avaient assisté". Registre supérieur, 1ère galerie, mur ouest, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur.

. Upon dismounting in the middle of a village, the Buddha's head is filled with marvellous if naive ideas about saving humanity, which he wants to share. However, the village inhabitants bow low to him as if he were on parade for them; no one is interested in what he has to say, and all they want is to revere him. He stupefies the village people by proceeding to undress before them; they remain prostrated, forcing him next to cut his hair

Détail du 67e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha (Bouddha) coupe ses cheveux, insigne de sa caste noble". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur ouest, quartier nord-ouest du Borobudur.

, since long hair was considered a privilege of the nobility. Still no reaction, so - as the supreme sacrifice - he removes his earrings, for in the East, the right to wear dynastic drop earrings was a symbol of royalty, even more so than the crown and scepter. Having divested himself of all, and appearing fully in the nude before the people, he at last dominates their typically Oriental (particularly in India) atavistic attitude and truly captures their attention. This scene has only rarely been depicted.

Hence, to portray the Buddha with distended ear lobes is to remind viewers/worshippers that, although he was entitled to wear earrings, he deliberately renounced them.

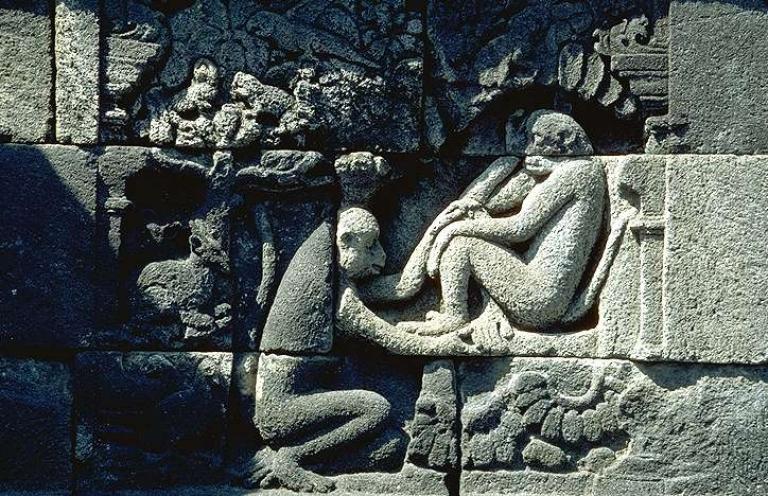

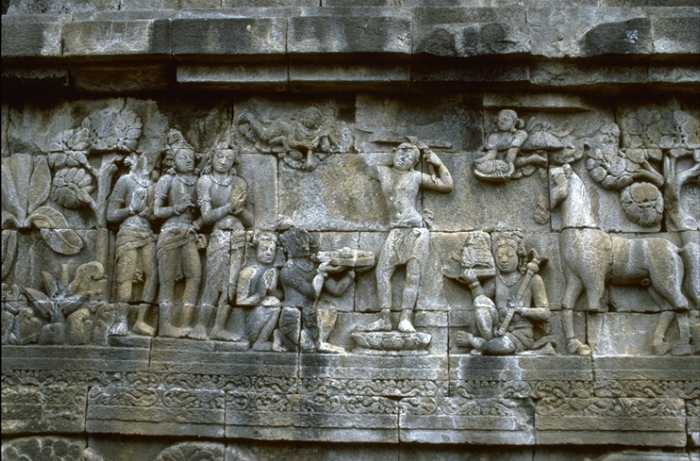

The Buddha follows the life of what are called the "sadhus" in India (Hindu term for holy men, especially monks). He leaves for the forest

The Buddha follows the life of what are called the "sadhus" in India (Hindu term for holy men, especially monks). He leaves for the forest  to meditate on the world, planning to return and offer the fruits of his meditation for the salvation of his fellow man. In this scene - which can also be found in the Sanchi (central India) stupa, the Ajanta (S. central India) grottoes, and the Ellora (S. central India) bas-reliefs - he leaves with other sadhus to experience self-imposed, full asceticism. He is generally portrayed during this period of his life as progressively thinner and thinner from episode to episode, until nothing but skin and bones - for example, in the Gandhara (ancient region in NW India and Afghanistan) bas-reliefs, where artists favored somewhat expressionist representations. He did in fact grow thinner together with the other sadhus, but came to realize the vanity of fasting. He rejected the conquest of his own body as belonging to the realm of pride, and then came to reject the conquest of the mind in the same spirit: rather than a pseudo death, life is simply to be lived if one wants to be able to give to others.

to meditate on the world, planning to return and offer the fruits of his meditation for the salvation of his fellow man. In this scene - which can also be found in the Sanchi (central India) stupa, the Ajanta (S. central India) grottoes, and the Ellora (S. central India) bas-reliefs - he leaves with other sadhus to experience self-imposed, full asceticism. He is generally portrayed during this period of his life as progressively thinner and thinner from episode to episode, until nothing but skin and bones - for example, in the Gandhara (ancient region in NW India and Afghanistan) bas-reliefs, where artists favored somewhat expressionist representations. He did in fact grow thinner together with the other sadhus, but came to realize the vanity of fasting. He rejected the conquest of his own body as belonging to the realm of pride, and then came to reject the conquest of the mind in the same spirit: rather than a pseudo death, life is simply to be lived if one wants to be able to give to others.

Having come to grips with the vanity of asceticism, he was ready to accept the first bowl of soup (or milk) from the hand of a woman called Sudjata, and, by the same token, ready to experience enlightenment.

Détail du 86e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddartha Gautama (Bouddha) se baigne dans la rivière Nairanjana". Registre supérieur, 1ère galerie, mur nord, angle nord-ouest du Borobudur.

Here the Buddha, followed by his disciples, is obliged to cross a river. The episode is an important one, occurring at a time when the Buddha is about to be reborn, this time to the Word, at Sarnath: the emergence of the Law at Sarnath. The river crossing, considered an initiatory rite in all the religions of the world, is always associated with the Buddha's renaissance, that is with his last birth, namely unto the Word.

This is such a turning-point in the life of the Buddha that it is considered his second birth.

94e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Alors que Siddhârtha médite sous l'arbre pippal, les hordes de Mâra, la Mort l'assaillent". Registre supérieur de la 1ère galerie (ou terrasse carrée), mur nord, quartier nord-est du Borobudur

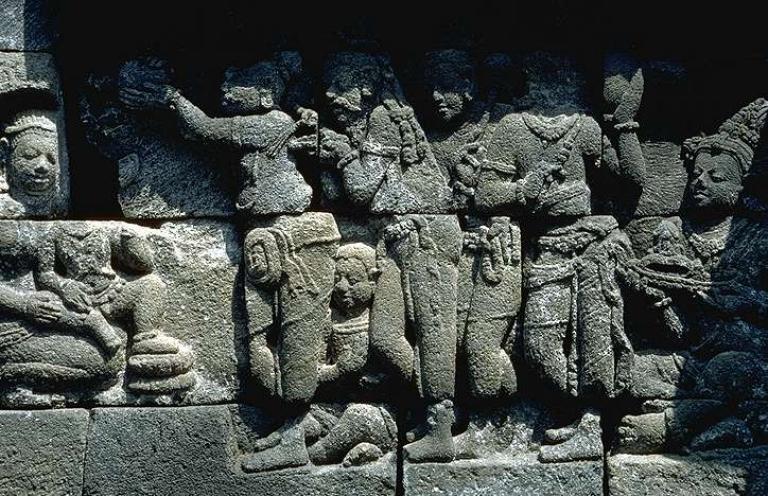

The panel on the temptation of the Buddha is of paramount importance. In the same fashion as Christ, the Buddha was tempted by the gods, who were uneasy with a mortal of such purity. Allegedly, it was Mara, the demon of temptation, who came, but according to the classical Lalita, it was all the gods - Vishnu ("the Preserver", second member of the Trimurti), Indra (god of rain and thunder), Surya (solar deity), etc. - who tried in vain to tempt him. They were never able to weaken the meditating Buddha's silence. The gods are depicted with their respective attributes: a wheel for Vishnu, a big curved saber for Shiva ("the Destroyer"), a hatchet for Durga (goddess of war), etc. The fact that it still portrays the Hindu gods makes this panel, the first Buddhist icon, the oldest and most venerable of such icons. The grottoes of Bhaja in India, featuring bas-reliefs carved 2 centuries BC, have a niche showing the Buddha surrounded by Surya on one side and Indra on the other - exactly the same subject. It is touching to note that the iconography remained altogether traditional despite the lapse of time, 1100 years to be exact. To tempt the Buddha, Mar (or Mara) even sent her daughters

Détail du 95e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Siddhârtha médite et les filles de Mâra tentent de le séduire". Registre supérieur du mur nord de la première galerie, quartier nord-est du Borobudur.

, an episode that is also depicted at Ajanta.

Détail du 118e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Ses anciens compagnons quêtent son enseignement". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur est, quartier nord-est du Borobudur.

The 120th panel of the first gallery deals with the 11th pivotal episode, representing the Buddha at Sarnâth

Détail du 119e des 120 bas-reliefs de la vie du Bouddha. "Il est ondoyé par ceux qui deviennent ses disciples". Registre supérieur de la première galerie, mur est, quartier nord-est du Borobudur

, in the Deer Park, where his third birth, unto the Word, takes place. From then on he will be enabled to teach and, amazingly, from then on there are no more episodes conveying the message of the Buddha in his daily life, for they are all contained in the sutras (sermons by the Buddha on Buddhism). In effect, all that the Borobudur Lalita narrates has to do with what preceded the Buddha's awakening to the Word, that is, his three births: the physical birth at Kapilavastu (Himalayan foothills of present-day S. Nepal), his birth to light at Bodh Gaya, and to the Word at Sarnath. The last birth, the absolute birth, the Purinirvana - known to us as death - is not shown to us. The Lalita comes to an end when the Buddha starts his sermons, and it is the sutras that go on from there. All this is beautifully documented in this first gallery, from which we are now ready to go straight to the top, to the World of Formlessness, the site of the One and Only.

- The Play in Full: LalitavistaraThe Play in Full

Summary

The Play in Full tells the story of how the Buddha manifested in this world and attained awakening as perceived from the perspective of the Great Vehicle. The sūtra, which is structured in twenty-seven chapters, first presents the events surrounding the Buddha’s birth, childhood, and adolescence in the royal palace of his father, king of the Śākya nation. It then recounts his escape from the palace and the years of hardship he faced in his quest for spiritual awakening. Finally the sūtra reveals his complete victory over the demon Māra, his attainment of awakening under the Bodhi tree, his first turning of the wheel of Dharma, and the formation of the very early SaṅghaIntroduction

The Play in Full (Lalitavistara) is without a doubt one of the most important sūtras within Buddhist Mahāyāna literature. With parts of the text dating from the earliest days of the Buddhist tradition, this story of the Buddha’s awakening has captivated the minds of devotees, both ordained and lay, as far back as the beginning of the common era.

In brief, The Play in Full tells the story of how the Buddha manifested in this world and attained awakening. The sūtra, which is structured in twenty-seven chapters, begins with the Buddha being requested to teach the sūtra by several gods, as well as the thousands of bodhisattvas and śrāvakas in his retinue. The gods summarize the sūtra in this manner (chap. 1): “Blessed One, there is an extensive collection of discourses on the Dharma that bears the name Lalitavistara (The Play in Full). This teaching illuminates the basic virtues of the bodhisattvas, showing how the Bodhisattva descended from the sublime palace in the Heaven of Joy, intentionally entered the womb, and sojourned in the womb. It shows the power of the place where he was born to a noble family, and how he surpassed others through all the superior special qualities that he demonstrated through his actions as a youth. It shows his many unique qualities, such as his skills in craftsmanship, activity, writing, arithmetic, calculations, astrology, fencing, archery, feats of physical strength, and wrestling, demonstrating his superiority to all other beings in these areas. It shows how he enjoyed his retinue of consorts and the pleasures of his kingdom. “This teaching proclaims how he attained the result brought about by the concordant cause of all the bodhisattva activities, showing how he manifested as a bodhisattva and destroyed the legions of Māra. It explains the ten powers, the four fearlessnesses, and the other innumerable qualities of a thus-gone one, and presents the infinite teachings taught by the thus-gone ones of times past.” The Buddha silently accepts this request, and the following day he commences the teaching.

The story begins in the divine realms where the future Buddha (who, prior to his awakening, is known as the Bodhisattva) enjoys a perfect life surrounded by divine pleasures. Due to his past aspirations, however, the musical instruments of the palace call out to him, reminding him of his prior commitment to attain awakening (chap. 2). Inspired by this reminder, the Bodhisattva announces, to the despair of the gods, that he will abandon his divine pleasures in pursuit of full and complete awakening on this earth (Jambudvīpa), where he will take birth within a suitably noble family (chap. 3). However, before his departure from the heavenly realms, the Bodhisattva delivers one final teaching to the gods (chap. 4) and, having installed the bodhisattva Maitreya as his regent, he sets out for the human realm accompanied by great displays of divine offerings and auspicious signs (chap. 5). He enters into the human world via the womb of Queen Māyā, where he resides for the duration of the pregnancy within an exquisite temple, enjoying the happiness of absorption (chap. 6).

After taking birth at the Lumbinī Grove and declaring his intention to attain complete awakening (chap. 7), we follow the infant Bodhisattva on a temple visit where the stone statues rise up to greet him (chap. 8) and hear of the marvelous jewelry that his father, the king, commissions for him (chap. 9). Next, as the Bodhisattva matures, the sūtra recounts his first day at school, where he far surpasses even the most senior tutors (chap. 10); his natural attainment of the highest levels of meditative concentration during a visit to the countryside (chap. 11); and his incredible prowess in the traditional worldly arts, which he uses to win the hand of Gopā, a Śākya girl whose father requires proof of the Bodhisattva’s qualities as a proper husband (chap. 12). The Bodhisattva has now reached maturity and can enjoy life in the palace, where he is surrounded by all types of pleasure, including a large harem to entertain him. Seeing this, the gods begin to worry that he will never leave such a luxurious life, and they therefore gently remind him of his vows to awaken (chap. 13). This reminder, however, turns out to be unnecessary, as the Bodhisattva is far from attached to such fleeting pleasures. Instead, to the great despair of everyone in the Śākya kingdom, he renounces his royal pleasures. Inspired by the sight of a sick person, an old man, a corpse, and a religious mendicant (chap. 14), he departs from the palace to begin the life of a religious seeker on a spiritual journey, which eventually leads him to awakening (chap. 15).

Already at this early stage of his religious career, the Bodhisattva is no ordinary being. It quickly becomes apparent that he surpasses all the foremost spiritual teachers of his day. His extraordinary charisma also attracts many beings, such as the king of Magadha, who requests the Bodhisattva to take up residence in his kingdom, but without success (chap. 16). In a final test of the established contemplative systems of his day, the Bodhisattva next follows Rudraka, a renowned spiritual teacher. But once again he is disappointed, although he quickly masters the prescribed trainings.

These experiences lead the Bodhisattva to the conclusion that he must discover awakening on his own, so he sets out on a six-year journey of austere practices, which are so extreme in nature that they take him to the brink of death (chap. 17). Finally the Bodhisattva realizes that such practices do not lead to awakening and, encouraged by some protective gods, he begins to eat a normal diet once again, which restores his former physique and health (chap. 18). At this point he senses that he is on the verge of attaining his goal, and therefore sets out for the seat of awakening (bodhimaṇḍa), the sacred place where all bodhisattvas in their last existence attain full and complete awakening (chap. 19). As he arrives at the seat of awakening, the gods create a variety of impressive miraculous displays, and the place eventually comes to resemble a divine realm, fit for the epic achievement that awaits the Bodhisattva (chap. 20)

Still, just as everything has been prepared to celebrate the attainment of awakening, Māra, the most powerful demon in the desire realm, arrives with the aim of preventing the Bodhisattva from attaining his goal. Together with his terrifying army and seductive daughters, Māra tries every trick in the book to discourage the Bodhisattva, but to no avail. Sad and dejected, Māra eventually gives up his disgraceful attempt at creating obstacles (chap. 21). Now the stage is finally set for the Bodhisattva to attain awakening under the Bodhi tree, a gradual process that unfolds throughout the night until he fully and perfectly awakens at dawn to become the Awakened One (Buddha), or Thus-Gone One (Tathāgata), as he is known subsequent to his awakening (chap. 22). As is only suitable for such an epic achievement, the entire pantheon of divine beings now hurry to the Thus-Gone One, making offerings and singing his praise (chap. 23).

During the first seven weeks following his awakening, the Buddha keeps to himself and does not teach. In fact he worries that the truth he has discovered might be too profound for others to comprehend, except perhaps a bodhisattva in his last existence. Māra, who senses the Buddha’s dilemma, turns up and tries one last trick, suggesting to the Buddha that perhaps this would be a suitable time to pass into parinirvāṇa! The Buddha, however, makes it clear that he has no such plans, and finally Māra relents. During these first seven weeks, we also hear of other encounters between the Buddha and some local passersby, but significantly no teaching is given (chap. 24). Setting up an important example for the tradition, the Buddha eventually consents to teach the Dharma only after it has been requested four times, in this case by all the gods, headed by Brahmā and Śakra. As he says, “O Brahmā, the gates of nectar are opened” (chap. 25).

At this point, the Buddha determines through his higher knowledge that the first people to hear his teaching should be his five former companions from the days when he was practicing austerities. Although these ascetics originally rejected the Bodhisattva when he decided to abandon their path, when they meet the Buddha again at the Deer Park outside of Vārāṇasī, they are rendered helpless by his majestic presence and request teachings from him. The five companions instantly receive ordination and, in a seminal moment, the Buddha teaches them the four truths of the noble ones: suffering, the origin of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the path that leads to the cessation of suffering. Thus this occasion constitutes the birth of the Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Saṅgha (chap. 26). This marks the end of the teaching proper. Finally, in the epilogue, the Buddha encourages his retinue of gods and humans to take this sūtra as their practice and propagate it to the best of their abilities (chap. 27).This story thus ends at the very moment when the Buddha has finally manifested all the qualities of awakening and is fully equipped to influence the world, as he did over the next forty-five years by continuously teaching the Dharma and establishing his community of followers. From our perspective, this may seem odd. Why do we not get to follow the Buddha as he builds his community of monks and nuns and interacts with the people of India, high and low, throughout his teaching career? And why do we not get to hear the details of his old age and passing into nirvāṇa? After all, this is the part of his life where his inconceivable qualities are most evident and where his glory as the fully awakened Buddha is most radiant.

The answer of course cannot be settled here, but we can at least surmise. Perhaps the aim of this account is not to describe the life of the Buddha in the way one would expect in a traditional biography, or even a religious hagiography. Instead the scope of The Play in Full may be to tell the story of the complete awakening of a bodhisattva in his last existence. The many events that occurred postawakening during the Buddha’s forty-five-year teaching career are therefore not of particular interest to a project that aims to describe the awakening of a buddha. These events, moreover, are well documented in the teachings preserved elsewhere in the Buddhist canon.

If this assumption is correct, The Play in Full should not be viewed exclusively as the “life of the Buddha” in the way we might ordinarily understand such a phrase, but rather as an account of the unfolding of awakening itself, clearly centered around the figure of Buddha Śākyamuni, yet with many themes and plots that do not exclusively refer to his particular life example. Although we do hear of events specific to the life of Buddha Śākyamuni in the chapters concerning his education, athletic prowess, and so on, we are often reminded that the main occurrences recounted in The Play in Full have unfolded previously, namely whenever past bodhisattvas awoke to the level of a thus-gone one. Thus this story represents nothing new under the sun; instead it recounts what happens to everyone who is in a position such as the Bodhisattva’s.

This brings up another important feature of The Play in Full, which is the ahistorical Mahāyāna backdrop that informs the entire story line. Throughout the text, the story is covered by a latticework of mind-boggling miracles and feats that defy comprehension by the ordinary intellect. Clearly, in the perspective of the Mahāyāna, the world is fashioned according to the lenses that we use to see with. And here, in The Play in Full, the lenses are those of full and complete awakening. This fact is already alluded to in the title of the text, which describes the events in the Bodhisattva’s life as a play. As such the events in the Bodhisattva’s life are not ordinary karmic activity that unfold based on the mechanisms of a conceptual mind, but rather the playful manner in which the nonconceptual wisdom of a tenth-level bodhisattva unfolds as an expression of his awakened insight. In this manner of storytelling, the reader is invited into the worldview of a timeless and limitless universe as perceived by the adepts of the Mahāyāna. The time span, numbers, and sizes within this Mahāyāna scripture are so persistently overwhelming that all historical and scientific thinking as we know it eventually loses meaning and relevance.

As such The Play in Full is not a historical document and it was probably never intended to be. Instead it is a story of awakening that itself contains all the key teachings of the Mahāyāna. Thus, to fully appreciate this text, the reader must also attend to its aesthetic and rhetorical functions and how its narrative progression and episodes have been designed to impact readers, rather than simply approaching the text as documentary evidence of a life well lived. The text can thus be read on many levels from a Buddhist perspective, with new facets being discovered upon each reading. For the layperson it may provide an inspiring glimpse into the ethos of the Mahāyāna worldview, for the renunciant it can represent an encouragement to live the contemplative life, and for the scholar it may appear as an exemplary specimen of Buddhist philosophy and literature. For others it may be all of these, and still more.

Still, the fact that The Play in Full is not a text meant to provide historical details of the founder of Buddhism should not prevent us, if we are so inclined, from enjoying this magnificent religious literature through the lenses of historical awareness and philological scholarship. If we choose to adopt such perspectives, The Play in Full does indeed contain a wealth of information of interest to the historically inclined. The basic framework for the story of the Bodhisattva’s awakening was already in place within the Buddhist tradition many centuries before this text’s composition, as early scholarship on the sūtra has already pointed out (e.g., Winternitz 1927). This essential framework, however, was greatly developed and adorned by the sūtra’s compilers/authors in order to create its current form, which Vaidya (1958) has dated to the third century C.E. Before that time, stories surrounding the life of the Buddha (and the Bodhisattva in his last and previous existences) were in place in the various canons of the early Buddhist schools. However, the extensive account of awakening according to the Mahāyāna perspective only manifests with the appearance of The Play in Full.

This scripture is an obvious compilation of various early sources, which have been strung together and elaborated on according to the Mahāyāna worldview. As such this text is a fascinating example of the ways in which the Mahāyāna rests firmly on the earlier tradition, yet reinterprets the very foundations of Buddhism in a way that fit its own vast perspective. The fact that the text is a compilation is initially evident from the mixture of prose and verse that, in some cases, contains strata from the very earliest Buddhist teachings and, in other cases, presents later Buddhist themes that do not emerge until the first centuries of the common era. Previous scholarship on The Play in Full (mostly published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) devoted much time to determining the text’s potential sources and their respective time periods, although without much success. For example, while the first critical publications argued that the verse sections of the text represent a more ancient origin than the parts written in prose, that theory had largely been dismissedby the beginning of the twentieth century (Winternitz 1927). Although this topic clearly deserves further study, it is interesting to note that hardly any new research on this sūtra has been published during the last sixty years. As such the only thing we can currently say concerning the sources and origin of The Play in Full is that it was based on several early and, for the most part, unidentified sources that belong to the very early days of the Buddhist tradition.

The Play in Full makes no attempt to present itself as a homogenous text composed by a single author. In fact it seems that the compilers of the text took pride in presenting an account of the Bodhisattva’s last existence that was as detailed and allencompassing as possible and thus, to this end, it was perfectly acceptable to draw openly on a variety of sources. One obvious example of this is the fact that although the story is for the most part recounted in the third person, it occasionally and abruptly shifts into a first-person narrative where the Buddha recounts the events himself. In addition, there is often a significant overlap between the topics covered in the prose and verse sections, and in these places the compilers of the text have made no attempt to polish away the inconsistencies and redundancies. It is likely that the discerning readers of the time may have been quite aware of the sources on which The Play in Full draws, and that it was perfectly acceptable at the time to compile a “new” scripture from traditional sources, and to have this newly assembled literature be afforded the same inspired status as other instances of “the words of the Buddha” (buddhavacana). Certainly the Mahāyāna literature contains many statements in support of such an open-ended approach to canonical standards.

The title of this sūtra indicates that this is an elaborate account of the playful activity performed by the Bodhisattva. The fact that it is called In Full (vistara) indicates that the compilers saw this text as an elaborate way of viewing the awakening of the Buddha, as opposed to other (from a Mahāyāna perspective) more limited accounts, which have less emphasis on miracles and elasticity of time and place. But In Full is not to be understood only in terms of the vast Mahāyāna worldview. It can also signify an elaborate account that includes more details than previous presentations of the topic, since the Sanskrit word vistara can communicate this meaning as well.

Both of these interpretations of vistara are also possible based on the translated title in Tibetan (rgya cher rol pa). Although the grammatical elements in the Sanskrit and Tibetan titles differ, the Tibetan title can nevertheless be interpreted in ways similar to the Sanskrit. As such the title of this text already gives subtle hints that the internal hermeneutics of this sūtra may differ from our contemporary historical perspective regarding definitions of “the words of the Buddha.” Instead, by embracing the worldview of playful activity that The Play in Full presents, the words of the Buddha can manifest at any time, whether compiled, edited, or even newly authored. In India, The Play in Full was no doubt a work in progress over several centuries before it finally settled into the form that we know today. It appears to have enjoyed a certain popularity in India, and it also had significant influence in several other Asian regions. In the Gandharan art of the period in which The Play in Full emerged, the themes of the text are widely represented in temple art, and even as far away as the Borobudur Temple complex in Indonesia, this sūtra provided the inspiration for the elaborate artwork adorning the temple structures. The Play in Full (or perhaps a prototype of it) may also have been translated into Chinese in the fourth century C.E., although this has not been confirmed.

We do have, however, a very beautiful and accurate Tibetan translation of the text. This was produced in the ninth century C.E. as one of the first translations ever made into that language, which attests to the text’s popularity and perceived importance at the time. This is the text that we have translated here. Once the text was available in a Tibetan translation, it quickly became the primary source for recounting the Buddha’s attainment of awakening and, unlike many other sūtras, The Play in Full appears to have been read and studied often in Tibet. While numerous scriptures from the Kangyur have slipped into relative obscurity, The Play in Full has continued to have a lasting impact on Tibetan Buddhism, all the way down to the present.

In the West, the first mention of The Play in Full occurred in 1874 when Salomon Lefmann published a Sanskrit edition of the text, as well as a partial translation into German. Shortly thereafter further translations appeared, including an English translation by R. L. Mitra in 1875, and most influentially a full French translation by Édouard Foucaux in 1892. Almost a hundred years later, Gwendolyn Bays, who based her work on Foucaux’s translation with reference to the original Sanskrit and Tibetan, published a complete translation in English.

This present translation builds on, and benefits from, the considerable efforts of these previous scholars. Unlike earlier translations, however, we have based our translation on the Tibetan text as found in the Degé Kangyur (Toh 95), with reference to the other available Kangyur editions. In addition we have also compared the Tibetan translation line by line with the Sanskrit (Lefmann 1874), and we have revised the translation on numerous occasions where the Sanskrit clarified obscure passages in the Tibetan version or represented a preferred reading.

As such it is fair to say that this translation as it stands is an equal product of the Tibetan and the Sanskrit. Although some scholars may have preferred a translation from the Sanskrit alone, we believe that the present approach is justified, since a comparative study of the available manuscripts makes it clear that several strands of manuscripts were extant in India, sometimes with significant differences in wording and content. Moreover, as the Tibetan manuscript predates the existing Sanskrit manuscripts by centuries, the Tibetan may indeed represent an earlier stratum that merits attention apart from merely complementing the Sanskrit.

In producing this translation, we have sought to incorporate the best of both manuscript traditions through a diplomatic approach that does not give preference to either language a priori. Since there are literally thousands of differences between the Sanskrit and the Tibetan manuscripts when all levels of variance are considered, we have avoided annotating each individual reading preference in the translation. Our motivation for this has been to present a translation that the general reader can enjoy without getting distracted by numerous philological discussions and annotations that would interest but a few scholarly specialists. Instead, for those who would like to study the translation together with the original manuscripts, we have included references to the page numbers of both the Sanskrit and the Tibetan manuscripts, providing the specialist with an easy means for comparative textual studies. In this way it is our hope that both the general reader and the specialist may find the present translation to be of benefit and inspiration.

Translated by the Dharmachakra Translation Committee

version 2.22

Published by 84000 (2013)

www.84000.c

This work is provided under the protection of a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution - Non-commercial - No-derivatives) 3.0 copyright. It may be copied or printed for fair use, but only with full attribution, and not for commercial advantage or personal compensation. For full details, see the Creative Commons license.The Play in Full - The Lalitavistara Sūtra (Wikipedia)The Lalitavistara SūtraThe sutra consists of twenty-seven chapters:

- Chapter 1: In the first chapter of the sutra, the Buddha is staying at Jetavana with a large gathering of disciples. One evening, a group of divine beings visit the Buddha and request him to tell the story of his awakening for the benefit of all beings. The Buddha consents.

- Chapter 2: The following morning, the Buddha tells his story to the gathered disciples. He begins the story by telling of his previous life, in which the future Buddha was living in the heavenly realms surrounded by divine pleasures. In this previous life, he was known as the Bodhisattva. The Bodhisattva is enjoying the immense pleasures of his heavenly life, but due to his past aspirations, one day the musical instruments of the heavenly palace call out to him, reminding him of his prior commitment to attain awakening

- Chapter 3: Upon being reminded of his previous commitments, the Bodhisattva announces, to the despair of the gods in this realm, that he will abandon his divine pleasures in order take birth in the human realm and there attain complete awakening.

- Chapter 4: Before leaving the heavenly realms, the Bodhisattva delivers one final teaching to the gods.

- Chapter 5: The Bodhisattva installs Maitreya as his regent in the heavenly realms and sets out for the human realm accompanied by great displays of divine offerings and auspicious signs.

- Chapter 6: The Bodhisattva enters into the human world via the womb of Queen Māyā, where he resides for the duration of the pregnancy within a beautiful temple, enjoying the happiness of absorption.

- Chapter 7: The Bodhisattva takes birth at the grove in Lumbinī and declares his intention to attain complete awakening.

- Chapter 8: The infant Bodhisattva visits a temple where the stone statues rise up to greet him.

- Chapter 9: His father, Śuddhodana, commissions marvelous jewelry for him.

- Chapter 10: The Bodhisattva attends his first day at school, where he far surpasses even the most senior tutors. This chapter is notable in that it contains a list a scripts known to the Bodhisattva which has been of great importance in the history of Indic scripts, particularly through the comparison of various surviving versions of the text.[2]

- Chapter 11: On a visit to the countryside as a young boy, he attains of the highest levels of samadhi.

- Chapter 12: As a young man, he demonstrates his incredible prowess in the traditional worldly arts, and wins the hand of Gopā, a Śākya girl whose father requires proof of the Bodhisattva’s qualities as a proper husband.

- Chapter 13: The Bodhisattva reaches maturity and is able enjoy life in the palace, where he is surrounded by all types of pleasure, including a large harem to entertain him. Seeing this, the gods gently remind him of his vows to awaken.

- Chapter 14: The Bodhisattva takes a trip outside of the palace walls to visit the royal parks. On this trip, he encounters a sick person, an old man, a corpse, and a religious mendicant. Deeply affected by these sights, the Bodhisattva renounces his royal pleasures.

- Chapter 15: The Bodhisattva departs from the palace to begin the life of a religious seeker on a spiritual journey.

- Chapter 16: The Bodhisattva seeks out the foremost spiritual teachers of his day, and he quickly surpasses each of his teachers in understanding and meditative concentration. His extraordinary charisma also attracts many beings, such as the king of Magadhā, who requests the Bodhisattva to take up residence in his kingdom, but without success.

- Chapter 17: The Bodhisattva follows Rudraka, a renowned spiritual teacher. He quickly masters the prescribed trainings, but once again he is disappointed with the teachings. The Bodhisattva concludes that he must discover awakening on his own, and he sets out on a six-year journey of extreme asceticism. These practices take him to the brink of death.

- Chapter 18: The Bodhisattva concludes that the austere practices do not lead to awakening and, encouraged by some protective gods, he begins to eat a normal diet once again, and regains his health.

- Chapter 19: Sensing that he is on the verge of attaining his goal, the Bodhisattva sets out for the bodhimaṇḍa, the sacred place where all bodhisattvas in their last existence attain full and complete awakening.

- Chapter 20: He arrives at the seat of awakening, and the gods perform a variety of miraculous displays, transforming the area so that it resembles a divine realm, fit for the epic achievement that awaits the Bodhisattva.

- Chapter 21: Māra, the most powerful demon in the desire realm, arrives with the aim of preventing the Bodhisattva from attaining his goal. Māra attempts to terrify the Bodhisattva with his powerful army, and to seduce him with his seductive daughters, but he is unable to divert the Bodhisattva from his goal. Māra gives up, defeated.

- Chapter 22: Now the stage is set for the Bodhisattva to attain awakening under the Bodhi Tree, a gradual process that unfolds throughout the night until he fully and perfectly awakens at dawn to become the Buddha ("awakened") or Tathāgata, as he is known subsequent to his awakening.

- Chapter 23: Recognizing his epic achievement, the entire pantheon of divine beings visits the Thus-Gone One, making offerings and singing his praise.

- Chapter 24: For seven weeks following his awakening, the Buddha remains alone in the forest and does not teach. He is concerned that the truth he has discovered might be too profound for others to comprehend. Sensing this dilemma, the demon Māra tries to trick the Buddha one last time. Māra visits the Buddha and suggests that perhaps this would be a suitable time to pass into parinirvāṇa! The Buddha rejects Māra’s advice, and finally Māra retreats. During these first seven weeks, the Buddha also encounters some local passersby, but no teaching is given.

- Chapter 25: The gods Brahmā, Śakra, and the other gods sense the Buddha’s hesitation. They visit the Buddha and formally request him to teach the Dharma. They repeat the request four times before the Buddha eventually consents. Upon his consent to teach, the Buddha says, “O Brahmā, the gates of nectar are opened”.

- Chapter 26: The Buddha determines that the most suitable students for his first teaching are his five former companions from the days when he was practicing austerities. The Buddha travels to Deer Park outside of Varanasi, to meet his former companions. Initially, the companions are suspicious of the Buddha for having given up their austerity practices, but they are soon rendered helpless by his majestic presence and request teachings from him. The five companions instantly receive ordination and, in a seminal moment, the Buddha teaches them the Four Noble Truths: suffering, the origin of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the path that leads to the cessation of suffering. Thus this occasion constitutes the birth of the Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Saṅgha.

- Chapter 27: This marks the end of the teaching proper. Finally, in the epilogue, the Buddha encourages his retinue of gods and humans to take this sūtra as their practice and propagate it to the best of their abilities.

The Lalitavistara Sūtra

It is important to note the difference in the niches which, on this first gallery, are arched to form a relatively simple architectural decor, whereas they are adorned with the famous kalamakaras (animal-headed fable creatures symbolizing defence) on the upper level: here we are still the realm of desires made manifest, whereas the realm of teachings lies just above. Such architectural allusions make matters perfectly clear to visiting pilgrims.

Thus, lying at our feet we have the square layout narrating life as set down by the Law. Above us is the round form bespeaking Unity and the Absolute. So this is exactly where the circle and the square

meet and thus it represents a vital passage

. Until here, everything was covered with bas-reliefs, from inside to outside the balustrades, whereas, upon arriving at the Supreme Unity, everything is altogether plain, entirely unadorned. Such purity, such original simplicity is truly ineffable. Even the Buddha himself is hidden from our view as an image, as if the Mahayanist monks had sought to recapture a certain Hinayanist density, since each of the small stupas prolonging the large central stupa contains a statue of the Buddha (some of which have since disappeared). All this immense space leads to the last circle, the absolute stupa that is the center of All.

A first probe inside Borobudur, in 1815, revealed that the central stupa was empty. There exists a running argument between all those who have studied this monument of vital significance - specialists in the history of religions and art historians - as to whether or not it once contained a statue. It was the personal opinion of Jacques-Edouard Berger that the crowning stupa was empty from the start, for the simple reason that in 1815 there was not yet any interest in Oriental art. If not stolen, then the statue might simply have been mutilated, but no fragments ever showed up. Should the crowning stupa have been left empty deliberately, the message most probably goes very deep, implying that we are in a realm beyond appearance, a realm of pure spirit. The empty stupa would hence represent the absolute symbol that, in this World of Formlessness, refuses reference to any form whatsoever.

Another thought comes to mind upon contemplating the central stupa and the sort of shower of stupas extending it: in the Purinirvana notion dealing with the moment when the Bouddha

gives up earthly life, the text speaks of his soul being scattered in the form of millions of souls throughout the universe. In this context, one can picture the central stupa as the Buddha, and all the smaller stupas as the spreading of his Law and Faith. And carrying the image even further, all these particles, which fill the universe in its entirety, reappear everywhere, even on the balustrades and on to the very bottom of the monument. In other words, the impression is that this is a deliberate attempt to convey the grandeur of the Buddha's message to the lowliest earthly levels: an amazingly abstract concept, as present to today's viewers as it must well have been to the pilgrims of over 1000 years ago.

Originally, we now know for a fact, the Borobudur monument contained 602 statues of the Buddha, rather than the 564, even 504, inventoried previously. Seven heads from this monument are at the Musée Guimet in Paris, two at a Boston museum, one at the Metropolitan, etc. But many statue heads have disappeared since the first small-scale cleaning ordered by the Briton Thomas Stamford Raffles in 1814, the first major restoration under the Dutch engineer Theodoor van Erp between 1907 and 1911, and UNESCO's joint project with the Indonesian government in the 1970s...

As for our visit today, now that we have arrived at the crowning stupa, successive vistas have been opened to us. Mainly, however, there is the feeling that the Buddha has accompanied us all along the way. This is Borobudur's main impact. Every niche bespeaks the Buddha's presence and, as the troubled pilgrim ascends slowly to the Unity at the top, he will find comfort and encouragement at every step. How marvellous to rest assured that the Buddha watches over the nature that surrounds and frames a monument built to reflect it.